I. Yo, privacy advocates – HIPAA does not apply to events

I am fascinated by culture “controversies” that amount to little more than Monty Python-style arguments. We seem to have a lot of that in the U.S. these days, some of which is refreshingly easy to address. One such issue involves the supposed right to protect one’s vaccination status from disclosure to prospective employers or event hosts. To relieve the dramatic tension, there is NO SUCH RIGHT.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accounting Act of 1996 is administered by the Department of Health and Human Services. Therefore, DHHS is probably a reliable source regarding the scope of the law it enforces. Here is what it has to say:

The HIPAA Privacy Rule establishes national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other personal health information and applies to health plans, health care clearinghouses, and those health care providers that conduct certain health care transactions electronically. The Rule requires appropriate safeguards to protect the privacy of personal health information, and sets limits and conditions on the uses and disclosures that may be made of such information without patient authorization. The Rule also gives patients rights over their health information, including rights to examine and obtain a copy of their health records, and to request corrections.

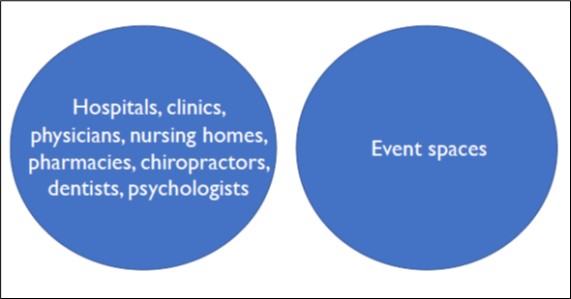

The Privacy Rule is located at 45 CFR Part 160 and Subparts A and E of Part 164. I do not recommend reading it unless you suffer extreme insomnia. As a public service, I offer the following handy Venn diagram to illustrate the intersection between the professions to which HIPAA privacy rights apply, versus those not subject to HIPAA. Feel free to share the image with any overzealous “privacy” advocates.

Fig. 1. Professions subject to HIPAA privacy provisions on left

2. Legal magic – how “invitees” turn into “trespassers”

I suppose I should be shocked and upset at the recent incidents of fan misconduct plaguing NBA arenas from Philadelphia to Salt Lake City. I am upset, but I may be losing the ability to be shocked by boorish behavior.

What has surprised me is that anyone questioned whether one can be banned and have their season tickets revoked for throwing stuff at players, loudly cursing their family in the stands, or trying to run onto the court during play. Who thinks there is a right to behave this way in someone else’s house? Evidently enough people that I was asked to explain the situation to the online publication Verify, which published an article and video called Yes, fans banned from arenas can face criminal charges if they return.

Most legal determinations require us to write and file pleadings that other lawyers respond to before a judge listens to arguments in court and then makes a preliminary ruling. This is different. One’s right to be on someone else’s premises is almost self-enforcing in its simplicity. Here’s how it works.

Every worker, guest, and performer at an event space is a “business invitee.” That invitation is conditional, meaning the party who extended the invitation can revoke it if the recipient violates the conditions. In a venue whose rules include “No shoes, no shirt, no service,” for example, the right to service is conditioned on covering one’s feet. Fan codes of conduct, which are ubiquitous at professional sports venues, articulate the terms on which fan invitations are conditioned.

The magic trick is that once someone violates a condition, their legal status automatically changes from invitee to trespasser. A “trespasser” is anyone on the property of another person or entity without permission. Just like your neighbor has no right to grab a beer from your refrigerator and park on your sofa, fans cannot assault players.

From there, it’s a slippery slope for the misbehaving fan. Once they have no right to be in the building, any season ticket, which is also a conditional invitation, can also be revoked. The fan may get some money back so the club can avoid the aggravation, but the fan will not be allowed to return. Attendance at events is a privilege, not a right.

Coda: Employment works the same way, especially in “right to work” states. Workers have no right to keep their job if they refuse to conform to their employer’s health and safety rules. Imagine if workers could decide for themselves whether to wear PPE on the job. The law provides ample support to resist that sort of thing.

3. Vaccine passports are legal, except where they’re not

I have written and spoken about vaccine passports a lot recently. I favor them for the simple reason that I favor reopening the event industry without causing avoidable sickness or death. To me, that seems pretty non-controversial. I acknowledge that certain elected officials see this differently. Turning once more to the wisdom of Monty Python, “[a]n argument is a connected series of statements intended to establish a proposition, … not just contradiction.”

So there.

If you wish to gather my pearls of wisdom on this subject, I am extensively quoted in this Meetings Today article, Vaccine Passports? Meetings and Events Experts Chime In. Subsequently, I participated in a thirty-minute throwdown about vaccine passports for the Event Leadership Institute. Suffice to say that I did not hold back.

4. If you’re vaccinated, come back in, the water’s fine!

In the interest of leading by example, I attended my first full-capacity live event since early 2020. I joined more than 8,000 new friends for a Phoenix Rising soccer match. (Thank you for the tickets, USL!) It was hot and crowded in the stands, almost no one wore a face covering, and there was no physical distancing. Because I have been vaccinated since February, I felt perfectly safe. Rising saved the day with a last-second goal that had the stands rocking with not a care in the world. It was great. There is just no substitute for live events. I hope to attend my first Major League Baseball game next week.

5. Coming attractions

I am excited to see event calendars and seats filling, at least in the States, which I hope will soon cause event professionals’ bank accounts to do the same. In the meantime, I have been feverishly writing and speaking in anticipation of life returning to something closer to normal.

Save room on your coffee table for the next issue of NFPA Journal, for which I have written the Perspectives article about the Lag B’Omer crowd crush in Israel. Preview: Event professionals will be interested in my theory about how individuals assume a “risk identity” when they participate in tribal activities, and lawyers will want to argue my contention that we need to rethink the “open and obvious hazard” defense in the context of live events.

Serious safety nerds (a term of praise and admiration) can sign up soon to buy the 2022 edition of the NFPA Fire Protection Handbook. This is an encyclopedic 3,500-page two-volume treatise covering every aspect of fire and life safety. NFPA says the current edition includes chapters by “254 leading authorities.” I am honored that my Chapter 4.4, Crowd Management, will replace one written by John Fruin, the father of American crowd management theory.

Finally, live performances are returning for me too. On July 15-16, I will be in Nashville with the Event Safety Alliance presenting at Summer NAMM, which is always a good time. In August, I will be speaking in Las Vegas and Orlando.

I look forward to seeing you out in the world. Steve Adelman