“I want what I want when I want it.”

This is the inner monologue of every event professional who looks longingly at their empty calendar, at each stress-inducing bank statement, at the cardboard “fans” who constitute our audiences. We all want to get back to work, back to play, back to being with family, friends, co-workers, total strangers, all without fear of infecting them or ourselves or someone we love with an insidious virus that has taken the lives of 491,455 Americans as I write this.

Sometimes, that desire makes us decide – simply decide – that what is unlikely or illogical must be true, because we’re fed up waiting for our damn complicated reality to deliver us from this maddening year-long holding pattern.

I ran across this situation in two recent news accounts about the very important question of when the United States is likely to reach “herd immunity.” This is when so many people are immune to a disease that even if they encounter an infected person, they still won’t get sick. Once herd immunity has been achieved, the disease no longer spreads within a population. In a nutshell, a surgeon wrote an opinion piece that was published in the Wall Street Journal that claims that the U.S. will reach herd immunity in April. This is fantastic news, exactly what we all want to hear. It is also belied by the consensus of mainstream epidemiologists, including those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who have long told us that although much depends on things we cannot currently know, such as the rate of vaccination and the likelihood that unvaccinated people will quit wearing face coverings in reliance on everyone else’s elevated resistance, their best current indication is sometime this Summer.

Critical thinking can help us sort out these competing assertions, so let’s try it. I’ll start.

Although I’m no doctor, I can tell that the WSJ opinion piece is written by a smart physician. I can read his bio, which appears impressive. I can also see that he is quoted often in conservative media, which is one clue among many, not a reason to blindly accept or dismiss what he says. So let’s look critically at the foundation upon which he lays a message that I desperately want to be correct.

Early in the piece, Dr. Marty Makary refers to “natural immunity,” and claims that it is “far more common than can be measured by testing.” That may be true, and as someone who traffics in terms like “reasonable under the circumstances,” I appreciate a subjective measure of the human condition at least as much as the next guy. But when he refers to non-empirical phenomena as “observational data” and claims that it is “compelling,” color me skeptical. Evidence is something I do know about. Observational data seems like another name for an anecdote, in the sense that it provides only as much information as one can observe. Extrapolating from subjective observations across large populations such as the United States is a recipe for “selection bias.” The legal analogy for scientific selection bias is “outcome determinative thinking,” in which the burden of proof one applies to a set of facts almost per se determines the outcome of the case. In other words, by choosing your yardstick, you effectively eliminate all but your preferred outcome. Less nerdy people might dismissively say “Garbage in, garbage out.”

Relying on selection bias to reach a preferred outcome is a neat trick if you can sell it. I think it’s worth asking why someone would predetermine their conclusion this way.

Dr. Makary, for example, implies that the “experts” are engaged in a conspiracy to hide favorable “data” about herd immunity because they are in bed with the American Federation of Teachers, which he suggests wants schools to resist in-person instruction as long as possible. My own observational data on this subject is that it was damn hard to teach my law students via Zoom, and I greatly preferred to see their looks of confusion and recognition in person.

Dispositive? Hardly. But my own experience does cause me to question the likelihood that the entire United States public health apparatus could collectively decide to hold back information that would hasten both our national economic and epidemiological health. Union experts can tell me otherwise, but I just don’t think the teacher’s union is so intimidating. And who keeps secrets so well? If there is some cabal of experts who are, for some reason, invested in slowing our national roll to recovery, how has this conspiracy come to exist with no one blowing the whistle until now? Conspiracies require 100% uniformity, absolute silence by every single person who knows anything about the shared information. In what circumstance of your life are you aware of people agreeing 100% on ANYTHING, much less on something that everyone is talking about all the time, on which our public health and economic recovery are both based??

My final thought about critical thinking is that it is useful to consider the consequences of going along with what looks sketchy just because someone says you can do it. Put another way, what if you act in reliance on Dr. Makary’s conclusion – you rescind all COVID-related health and safety rules and throw your doors wide open in April – and he’s wrong? We’ve seen that movie several times since last March. Infections and deaths spike, hospitals fill, venues close yet again, workers are sent back home once more. Rinse, repeat.

No thank you.

To me, the wiser course, as well as the more reasonable course under the circumstances of people who are eager to return to work once and for all, who believe in managing their risks, and who insist on reopening our industry in a way that puts life safety first, is to rely on the evidence-based science from CDC and other mainstream infectious disease experts.

I want what I want when I want it. But I want to reopen safely, with all of you.

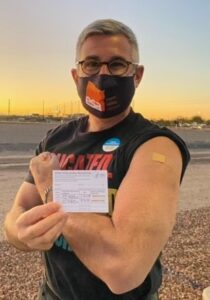

Vaccination is Sweet Soreness

Vaccination is Sweet Soreness

Because Arizona teachers, including law school faculty like me, have early access to the Pfizer vaccine, I was fortunate enough to receive my second shot last evening. I hear that some people feel sick the day after their second shot, but other than a sore arm, I feel just fine. I am emotionally relieved already, and I anticipate a sense of euphoria when I can do something with other people.

I look forward to seeing you again.