This semester marks the third time I am teaching Risk Management in Venues through Arizona State University’s Sports Law and Business program. As with my focus on risk and safety at live events, which is not really a thing for most lawyers, I had to invent my course from scratch. In an industry that doesn’t have much written guidance generally, there is no law school textbook to teach what I think about all the time.

I try new methods and materials each year. If you ever thought about going to law school, or wonder what lawyers really do, here are a few highlights from my class.

INSTRUCTIONAL PHILOSOPHY

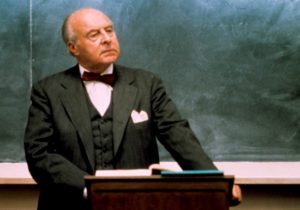

I do not lecture. Adults, including young adults, learn best by doing and speaking. I encourage enthusiastic and thoughtful discussion. Happily, I have bright students. I suppose it helps that I learned everyone’s names by the second class, so no one can hide. I care much less about conclusions than how we get there. In this respect, I follow the classic (fictional) pedagogical method of Professor Charles Kingsfield from The Paper Chase:

You teach yourselves the law. I train your minds. You come in here with a skull full of mush. You leave thinking like a lawyer.

You teach yourselves the law. I train your minds. You come in here with a skull full of mush. You leave thinking like a lawyer.

COURSE MATERIALS

Law school casebooks have been boring and hard to read since before I attended law school. So I assign two books that are neither: Amanda Ripley’s The Unthinkable, about how people respond in disasters, and John Barylick’s Killer Show, about the horrific Station nightclub fire, written by the leading plaintiff’s lawyer in the subsequent litigation. I supplement these with judicial decisions, pleadings filed by lawyers, expert reports, and documents produced during discovery.

Much of what I teach is a reaction against my own education. When I was a law student, I never saw any legal work product until I got a part-time job and started rifling through file drawers. This is the reason law students graduate with no clue how to practice law. So I show my students all of the behind the scenes work that constitutes the daily existence of most lawyers.

HOW TO LEARN FROM CATASTROPHES

I rely on an ancient instructional device: schadenfreude. Schadenfreude is a German (and Yiddish) word that means taking pleasure in other people’s misfortune. We laugh when Lucy pulls the football away from Charlie Brown, even though, if we thought it through, we’d realize that poor Chuck is probably looking at a concussion and some chiropractic treatment. If schadenfreude were only cruel, it wouldn’t be very useful (or funny). The reason I use it is that after we finish laughing, we should be left with a lingering question – would I have done anything differently?

I rely on an ancient instructional device: schadenfreude. Schadenfreude is a German (and Yiddish) word that means taking pleasure in other people’s misfortune. We laugh when Lucy pulls the football away from Charlie Brown, even though, if we thought it through, we’d realize that poor Chuck is probably looking at a concussion and some chiropractic treatment. If schadenfreude were only cruel, it wouldn’t be very useful (or funny). The reason I use it is that after we finish laughing, we should be left with a lingering question – would I have done anything differently?

Faithful readers know that everyone has a legal duty to behave reasonably under their own circumstances. In order to evaluate the reasonableness of other people’s conduct, we must develop a sense of empathy. To the extent possible with intelligent, sometimes overconfident young adults, I teach them to consider, there but for the grace of G-d go I.

THE BIG PICTURE

My own area of expertise is a Black Swan. What I deal with is highly unusual; the facts of my cases are strange and amazing; and after reading them, I encourage my students to think how the crazy mishaps that occur at live events are not so different from the more routine mayhem happening all around us, if only we look more closely.

I suspect that few of my students will get sports or entertainment jobs right out of law school. Really, I’m teaching advanced torts and contracts, and also how to see situations like a lawyer. Those are skills that should serve them well in whatever field they ultimately land.

I am consistently amazed at how little people notice the insanity all around us. Situational awareness? See something, say something? Not usually. At my course’s most basic level, that’s what I’m trying to do something about.