Standards are in the air I breathe. I use safety materials in my work, and I also lead groups creating new standards. I bring this up because in several recent conversations, otherwise intelligent people suggested that if there wasn’t a written treatise directly on point for their specific issue, then their client could have made any choice, taken any action, because there was no guidance at all. I’m not always quick enough to respond in the moment. But after a modest amount of reflection, I will share some thoughts in case someone drops the same illogical, unsafe line of reasoning on you.

WHAT IS A STANDARD, AND HOW IS IT DIFFERENT THAN A LAW?

Let’s begin with some proper nouns to ensure we’re referring to the same things.

Lots of peer-reviewed standards are issued by reputable organizations such as the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), ASTM International (formerly the American Society for Testing and Materials), and the Technical Standards Program of the Entertainment Services and Technology Association (ESTA). The Event Safety Alliance creates American National Standards through this latter process.

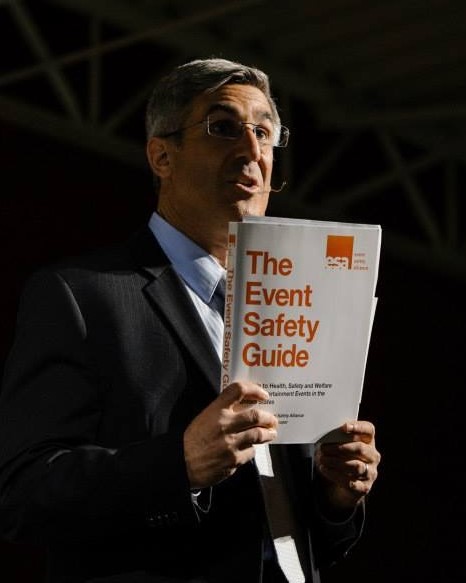

Industry associations apply their subject matter expertise to create further guidance, such as ESA’s Event Safety Guide, as well as materials by the National Center for Spectator Sport Safety & Security (NCS4) and the International Association of Venue Manager (IAVM). These do not go through as robust a public review process as a standard, but they are sometimes more operationally detailed because they are written for industry insiders.

Neither standards nor industry guidance carry the force of law when they’re issued. Legislators can adopt specific provisions or an entire document into the law of their jurisdiction if they can get a bill signed. For example, some cities adopt portions of the International Fire Code (IFC). There are also safety and health regulations like OSHA that are meant to interpret laws. Regulations, too, can incorporate standards or guidance, and also like laws, they are formed in the crucible of political compromise.

For a variety of perfectly logical reasons, most guidance about largely unregulated industries like event production and operations never draws the attention of legislators. Off the top of my head, I imagine legislators don’t generally know what we do, don’t particularly care, don’t have constituents who care unless something goes very wrong in their legislative district, and don’t have a political reason to learn how events work.

Thus, safe practices at events are often based on industry-generated standards and guidance. This is fine. I am often amazed to discover granular information on a subject one wouldn’t imagine deserves much attention. It is particularly impressive given how difficult it is to get a standard or treatise published. It took four years until ANSI ES1.9-2020, Crowd Management was published. When ANSI ES1.40-2023, Event Security is finalized in the next few months (fingers crossed!), that will have been another four-year project. We are just beginning the second edition of the Event Safety Guide – let’s see how long that takes.

AN INDUSTRY STANDARD NEED NOT BE WRITTEN TO BE A STANDARD

In my recent conversations, the rigid thinkers I mentioned suggested that a thing unwritten is a thing that does not exist. I knew this was wrong, but I lacked a smart response on the fly. The next time someone claims that a rule must be written somewhere or it cannot possibly be a rule, I will think of this excellent scene from A Few Good Men.

Capt. Ross: Corporal Barnes, I hold here the Marine Outline for Recruit Training. You’re familiar with this book?

Cpl. Barnes: Yes, sir.

Capt. Ross: Have you read it?

Cpl. Barnes: Yes, sir.

Capt. Ross: [hands him the book] Good. Would you turn to the chapter that deals with code reds, please?

Cpl. Barnes: [confused] Sir?

Capt. Ross: Just flip to the page of the book that discusses code reds.

Cpl. Barnes: Well, well, you see, sir code red is a term that we use. I mean, just down at Gitmo. I don’t know if it’s actually…

Capt. Ross: Ah, we’re in luck then. Standard Operating Procedures, Rifle Security Company, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Now, I assume we’ll find the term code red and its definition in that book. Am I correct?

Cpl. Barnes: No, sir.

Capt. Ross: No? Corporal Barnes, I’m a Marine. Is there no book, no manual or pamphlet, no set of orders or regulations that lets me know that, as a Marine, one of my duties is to perform code reds?

Cpl. Barnes: No, sir. No book, sir.

Capt. Ross: No further questions.

[as Ross walks back to his table Kaffee takes the book out of his hand]

Kaffee: Corporal, would you turn to the page in this book that says where the mess hall is, please?

Cpl. Barnes: Well, Lt. Kaffee, that’s not in the book, sir.

Kaffee: You mean to say in all your time at Gitmo, you’ve never had a meal?

Cpl. Barnes: No, sir. Three squares a day, sir.

Kaffee: I don’t understand. How did you know where the mess hall was if it’s not in this book?

Cpl. Barnes: Well, I guess I just followed the crowd at chow time, sir.

Kaffee: No more questions.

LAWYERS APPLY AND DISTINGUISH AUTHORITY ALL THE TIME

I should have been amused by the hypocrisy of lawyers claiming that guidance is valid only if it contains the exact words in their question. You see, we are trained to view existing authority as only a starting point for a legal argument. Despite the countless lawsuits filed over the history of this country, rarely will there have been exactly the same facts and legal issues in dispute. So lawyers on one side will find a result and reasoning they like, then insist the key facts are close enough to their case so the favorable ruling should apply to them too. The lawyers on the other side will insist that those same facts don’t apply in order to say that a case that favors their side is best.

Lawyers never find perfect authority – close enough is as good as we get. Standards are the same. It would be easier if there was a written standard – or even better, a law on the books – that exactly fit the facts of every situation we encounter in our work. But that’s not reality. Instead, we apply facts that look similar and we extrapolate those lessons, then we distinguish facts and rules that don’t fit our circumstances as well.

PERFECT IS THE ENEMY OF GOOD

As much as I like the scene in A Few Good Men, it is easier to prove that our decisions and actions are reasonable if we follow some kind of written guidance. That’s why some of us work so hard to create more of it. As of this Adelman on Venues, I am simultaneously editing the Global Crowd Management Association’s Field Guide to Crowds, drafting an American National Standard for Parade Safety, and organizing the second edition of ESA’s Event Safety Guide. If you want to get involved in any of these important projects, just email me. You’ll meet a bunch of smart friends, and you’ll help reduce my own stress levels.

I do this despite the certainty that as hard as we try to address every foreseeable risk, we will leave topics undiscussed. Something at a future event will occur that the drafters of industry authority did not precisely anticipate. A lawyer will thunder in the resulting lawsuit that there is no industry standard for some routine operational practice or niggling detail. They may be right, which will still miss the point.

We all interpret rules, seeking to tease out the lessons even from situations that don’t precisely match our own. This is how we learn from other people’s incidents and near-misses, rather than having to make every mistake ourselves.

We need to write more standards and guidance, mostly because we want to work as safely as we can. Also, the more we document reasonable ways to do what we do, the more likely we are to have a wise comeback ready when a lawyer starts thundering at us.